Introduction

Here at Star Name Registry, we take great pride to ensure every ‘name a star’ gift we give out is done in the spirit of the moon landings – to bring all of us a little closer to the stars. To those of us who take star registration and the ability for one to dedicate a star and adopt a star very seriously few things are as inspiring as the moon landing in 1969.

40 years passed, and the great space age we were all promised never quite arrived, when a little film was made by Duncan Jones called Moon came along. Jones, who was better known as David Bowie’s son before his breakout film, had over a decade of direction experience making adverts, and music videos. Moon was his first full length feature film and certainly a very impressive career start.

Homaging great Science Fiction classics like Silent Running, Bladerunner, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Solaris and Outland, Moon is a rare creature in the modern cinema landscape: a thought provoking science fiction drama – short on action and heavy on ideas.

We’re big fans of Duncan Jones and his films here at Star Name Registry – though his last two films, Warcraft and Mute haven’t been that well received we thought they were great and need a lot more love!

We thought we’d write a review / reflection on this little masterpiece of a movie, and maybe it’ll inspire you to Name a Star that shines brightly alongside the glowing moon.

Plot (SPOILERS AHEAD)

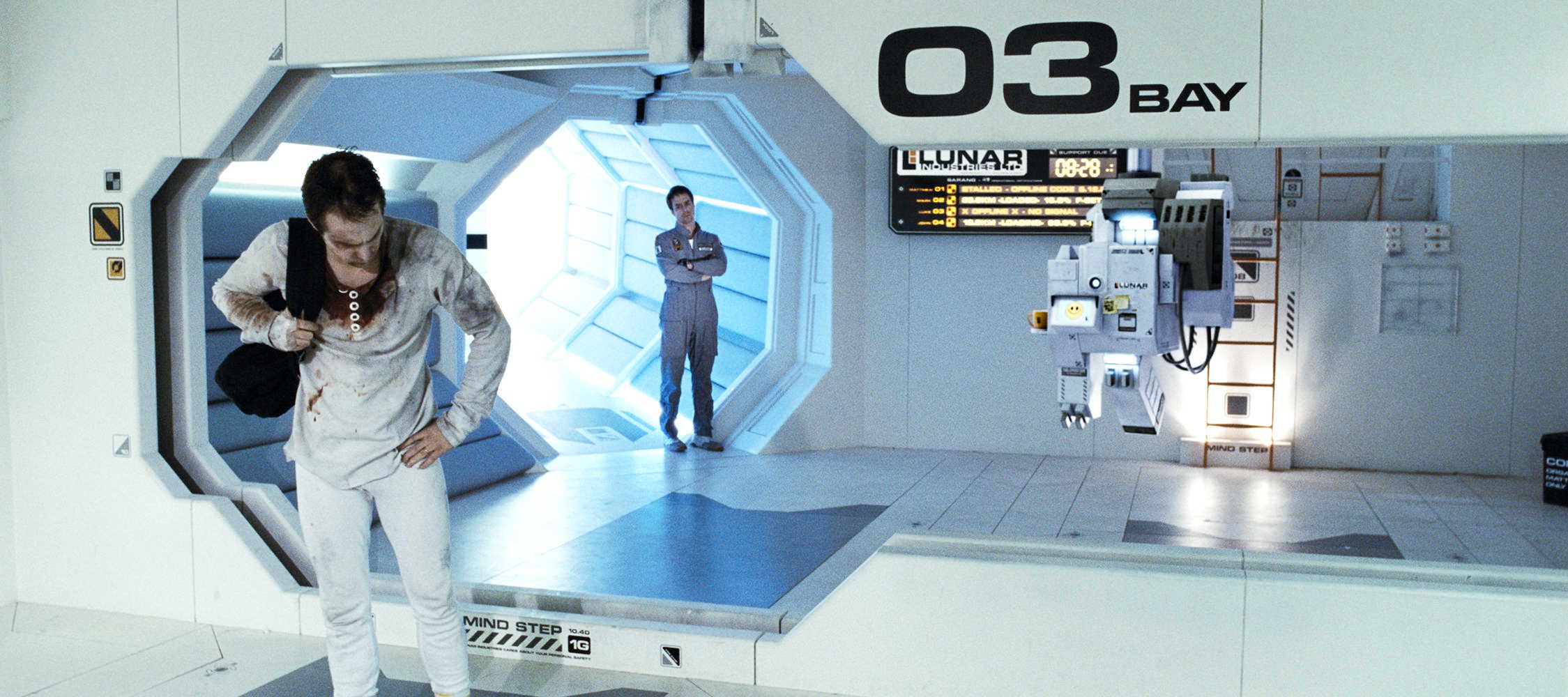

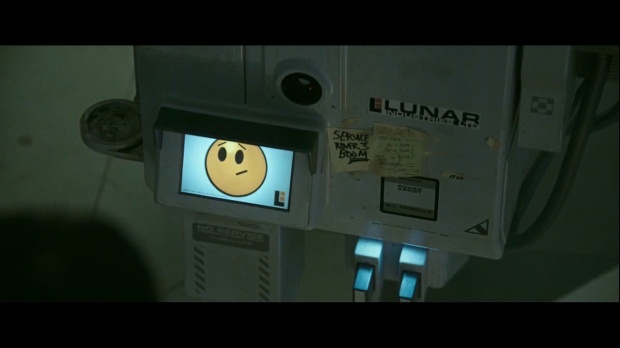

Set in the future, the energy crisis has been single handily resolved by a private corporation, Lunar Industries. They specialise in mining fuel from the moon (specifically an element called Helium 3) and using it for fusion reactions. Sam Rockwell plays Sam Bell, an astronaut working for Lunar Industries. He’s been assigned to a three-year stint working on the mostly automatic Lunar Base. Sam is the sole human on this base and he is mostly there to ensure there is a human presence who can be adaptive and creative in unexpected situations. He has an AI companion, a machine called Gerty who functions as caretaker, and who communicates with a calming voice and selected emojis on a screen.

The three years in space have taken huge a toll on Sam, both physically and mentally. Issues with the communication array have meant that live communication is impossible, and he must rely on recorded messages sent with a time delay. However, Sam is optimistic as he will be heading home very soon. While he’s been away, his wife Tess has given birth to a baby girl and is looking forward to meeting his new child. As he works, he is plagued by hallucinations of his life back home and his physical health seems to be deteriorating very quickly.

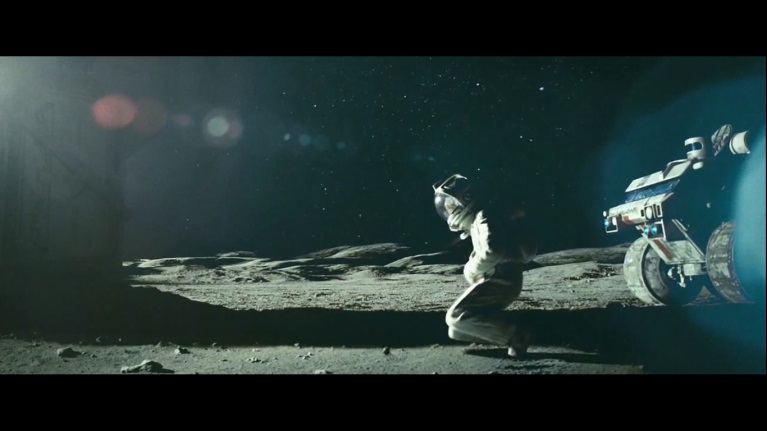

When one of the giant helium-harvesting machines breaks down, Sam goes out in a Lunar rover to fix it. His hallucinations return, and he crashes the rover.

We then cut to Sam waking up in the infirmary. Gerty tells him he has been unconscious for a few days and has suffered some memory loss. However, Gerty is acting in a way that arouses suspicion, so Sam heads outside to the rover where he finds… the other Sam!

(For simplicity, the Sam that crashed the rover will be Sam 1 and the one who just awoke will be Sam 2)

Sam 2 brings Sam 1 back to the base. Gerty confirms they’re clones of the original Sam Bell, with his memories implanted so they can run the base as the original once did. Each clone lasts only three years, before they begin to deteriorate. When one clone becomes too degraded to function, it goes into what they think is a transporter back to Earth, when in reality it is in an incinerator that kills the clone.

There’s a hidden chamber of other Sam Bell clones that Sam 2 discovers, with enough copies to keep the base manned for almost 500 years.

While that is going on, Lunar Industries guesses there’s something not quite right and announces that a rescue unit is on its way to repair the broken harvester. If the two Sams are discovered together they’ll likely be killed so they plan to a way to escape from the Moon base.

While they still have time Sam 1 figures out how to establish contact properly with Earth by traveling outside his working perimeter. He calls his wife Tess at their old home but manages to only get through to his now 15 year old daughter Eve, who tells him Tess died years ago.

Distraught, knowing only one of them can escape in a transporter, and near-death Sam 1 asks Sam 2 to put him back in the crashed rover to be found by the rescue unit – giving Sam 2 enough time to escape.

Gerty volunteers to erase its memory banks so that there will be no record of what has happened, ensuring Sam 2 has enough time to get to Earth and claim asylum and protection from Lunar Industries. The rescue unit docks, a new Sam awakes, and Sam 2 blasts off in the transporter; the dying Sam 1 watches him go and as he approaches Earth we hear audio of news reels discussing the political fallout of what Lunar has done.

While the film of Moon ends there, a few strands are alluded to in Duncan Jones’s later film ‘Mute’ which is set in the same universe but tells a completely different story. No spoilers for Mute ahead, most of these scenes are background events that don’t contribute to the plot of that film.

We see – as indicated by the voiceovers, that Sam’s return has caused a stir on Earth, with rolling news covering the fallout almost constantly. In one shot, we see the original Sam Bell being questioned by a government committee alongside they many clones that were hidden on the base.

“The 156 face their maker – Lunar Industries ex-employee questioned by panel in the presence of scores of his clones,” reads the ticker at the bottom of the rolling news coverage.

While we get no final closure on what happens exactly, the impression is that public is very sympathetic to Sam 2 and the plight of his fellow clones and that he may be due a happy ending after all. Jones has confirmed that he would want to make another sequel and wrap up the story even further – but for now we get a conclusive ending to an intriguing story.

Science

As for the science in the film, it follows a Hard Science logic, basing all the technology on our current understanding of science.

The way the moon base – while sporting a retro feel – functions is close to how scientists believe one might work. Gerty as an AI is also fairly accurate to how AI might develop in the future – he is certainly very effective but lacks doing much beyond his programming parameters and can’t be creative the same way a human being can. It’s been suggested that Gerty is following the Three Laws of Robotics, as outlined by Isaac Asimov. While still science fiction as this point, futurists consider these Three Laws a potential development in the creation of AI.

There’s also the question of Helium 3 as a power source, that can power 70% of the worlds energy requirements. This is theoretically possible and quite correct.

To understand how it’s accurate, we must understand the two different types of nuclear power: nuclear fission and fusion. Put in very simple terms, Fission is the splitting of a heavy atom into two lighter atoms. This process is what creates modern nuclear power plants and the atomic bomb. Fusion on the other hand, is the process where two light atoms combine releasing vast amounts of energy, and it’s the means by which the sun creates all its energy. Moreover: the lighter the stuff that undergoes fusion, the more energy you get. So ideally you should use Hydrogen, but as it turns out that Helium 3 seems to be easier to use.

So where does Helium 3 come into this? Helium 3 is a light isotope of regular Helium. (Put very simply, an isotope is a different version of the more common form of an element- It has the same number of protons and electrons but has a different number of neutrons)

Assuming that humanity was able to successfully replicate nuclear fusion, Helium 3 would be one of the main elements we’d consider using for fusion reactions. With this, it is likely that just 40 metric tons would be adequate to power the U.S. for an entire year (though this is in dispute amongst scientists). Another main advance of generating energy likes means that humanity could generate a highly efficient form of nuclear power with virtually no waste and no radiation.

However, this is dependent on very important thing – if the fusion process could be perfected. Fusion requires extremely precise and controlled temperature, pressure, and magnetic field parameters for any net energy to be produced. (Net energy meaning more energy is generated than being put in) Nuclear fusion reactors using helium-3 would need constant attention to work effectively, requiring dozens of highly trained nuclear scientists monitoring the reactor at any given time.

Other elements that might be an option for fusion reactions include deuterium, tritium, hydrogen and regular helium. Some scientists think it might be the case that tritium works better but is much more difficult to get than Helium-3, so for now mining helium-3 off the moon certainly seems like a good option.

The cloning aspect of the film is rooted more in science fiction than hard science, however. The term cloning describes several different processes that can be used to produce genetically identical copies of a biological entity. However, to clone person in the manner we see in the film might be impossible.

Dolly the sheep is the most famous clone that has existed thus far, and there’s some misunderstanding of how she came to be. She wasn’t strictly a copy of the original sheep per se, she shared the DNA of her ‘ancestor’ when she was born but had none of the memories of the original.

And Dolly couldn’t be the same age as the original, she had to be born as an infant live her own life, develop her own experiences. Aside from the difficulty of creating a biological copy of a subject that’s the same age at the time the genetic material is taken, transferring memory to a clone is WAY beyond anything mankind could reasonably achieve at this point in history.

Even with homozygote (identical) twins, who are genetically identical, studies have shown that environmental factors shape their biochemical composition. And even in close environments, Twins do develop their own personalities independent of each other.

And even if you could clone a subject as an adult, it’s very unlikely you could completely replicate their morphology in a laboratory. Every biological creature undergoes unique adaption in the environment in which they live.

So while it makes for a great story, the cloning aspect of the story is one of the bigger stretches in terms of science in the film. There are simply too many factors to account for when generating a biological copy of a subject, not to mention there exists no theoretical basis to copy and transfer memory to a possible clone. It’s a common misunderstanding that is widespread throughout sci-fi that one’s genetics and one’s identity inform each other.

However, while it’s interesting to deconstruct the science behind the film, in the end the science is not really THAT important. What is important is the story and the meaning behind the story. Science Fiction as a genre works well at addressing more complex questions about the human condition because it transforms the context from the abstract to the literal.

The film, therefore, is not interested in literally offering up the moral questions of using human clones as potential exploitable labour- but uses that context to engage its audience with a much more interesting question.

“If you were to meet yourself, would you like them?”

Analysis

Moon is not by any means a simple film to digest – it’s got a myriad of complexities that linger within its 90 minute running time that deserve to be fully unpacked.

At its most basic level, Moon could be viewed as a Marxist critique of how corporations exploit their workers under modern day capitalism. Sam is reduced to a literal commodity, a clone who gives up his labour time to the company, is given false promises about a happy home life and denied any real human contact.

While that interpretation does inform the some of the background ideas of the film, Jones takes a much bolder and nuanced approach by delving into critiques of a much greater philosophical importance – specifically as it pertains to identity and whether an artificial being can be considered to have a soul.

If one looks to psychoanalysis the film might represent a dramatic example of Jacques Lacan’s notion of the mirror stage – and how ideally it can be used to enrich our own conscious understanding of the self.

The Mirror Stage is often interpreted simplistically, as a belief that infants initially recognise themselves in a form that exists outside the body. Science has shed some doubt as to whether this is something that literally happens, but there’s an argument to be made that the mirror stage should be used more as philosophical context and perhaps we should view the mirror as metaphor for how we perceive ourselves when confronted with outside representation.

What one experiences when seeing themselves in a mirror, or video footage, or a photograph or even a drawing of them, it creates a structure of subjectivity in how we relate ourselves. Subjectivity in this case being defined as an explanation for that which influences, informs, and biases people’s judgements about truth or reality. The mirror stage relates to subjectivity, by informing how develop our own narrative about our own identity.

In other words, seeing a representation of ourselves, outside the physical experience of the body, allows us to relate and perceive ourselves in a way that allows us to construct and refine our ego and sense of identity.

What happens to Both Sam 1 and Sam 2 when they meet each other forces them to seriously critique their own self-perception.

Sam 1, having spent three years on the moon alone, has developed a compassionate, reflective and peaceful nature, his isolation having forced a more reflective attitude. Sam 2, as far he is concerned is just starting his mission and has more aggressive, hot-headed, and more willing to escalate conflict.

Both see representations of themselves that confront their individual perceptions of who they are as individuals, and subsequently they re-evaluate their own notions of identity.

Sam 2 is able to develop a strong sense of compassion for this fellow clone and for wider humanity as a result. Sam 1 begins to not judge himself so harshly for his past failings. Their ability to see familiarity and differences in each other elevates them both as individuals.

Conclusions

With a film that deals directly with ideas of exploitation and human rights, once might expect a more severe and critical film that looks to make the viewer enraged. Moon avoids this, making the overall mood of the film melancholy. Much like the character of Sam 2, the film wants the audience to be reflective of Sam’s situation, not indignant.

It follows in the tradition of classic 70’s and 80’s science fiction films that aimed to capture the deflation of optimism after the hype of the moon landings. With all good science fiction however, it must read as allegory rather than futurism. The question each viewer must ask themselves is, ‘How does this relate to the present state of humanity and what can this tell me about myself?’

Well that was a rather deep blog post! If you like what you read, and you’re a fan of Duncan Jones work he’s on Twitter @ManMadeMoon. If you liked the film and want to see some similar movies that inspired it, check out these classics of Science Fiction – Outlander, Solaris, Silent Running, Alien, 2001 a Space Odyssey, and Blade Runner!

If you’re looking to Name A Star, Dedicate A Star, or Adopt A Star for that special someone you can do so by following the link below!

Did you like this review? Let us know on our Facebook page or Twitter feed! Or if you can convey your feelings with a photo, send us a pic on Instagram!